This article has been machine-translated from Chinese. The translation may contain inaccuracies or awkward phrasing. If in doubt, please refer to the original Chinese version.

Concurrent Programming

-

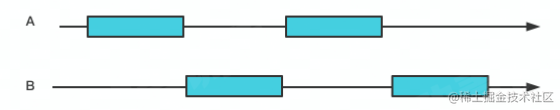

Concurrency is when a multi-threaded program runs on a single-core CPU

-

Parallelism is when a multi-threaded program runs on multiple cores

-

Go can fully leverage multi-core advantages for efficient execution An important concept

Goroutines

- Goroutines have less overhead than threads and can be understood as lightweight threads. A Go program can create tens of thousands of goroutines.

In Go, starting a goroutine is very simple - just add a go keyword before a function to start a goroutine for that function.

CSP and Channel

CSP (Communicating Sequential Process)

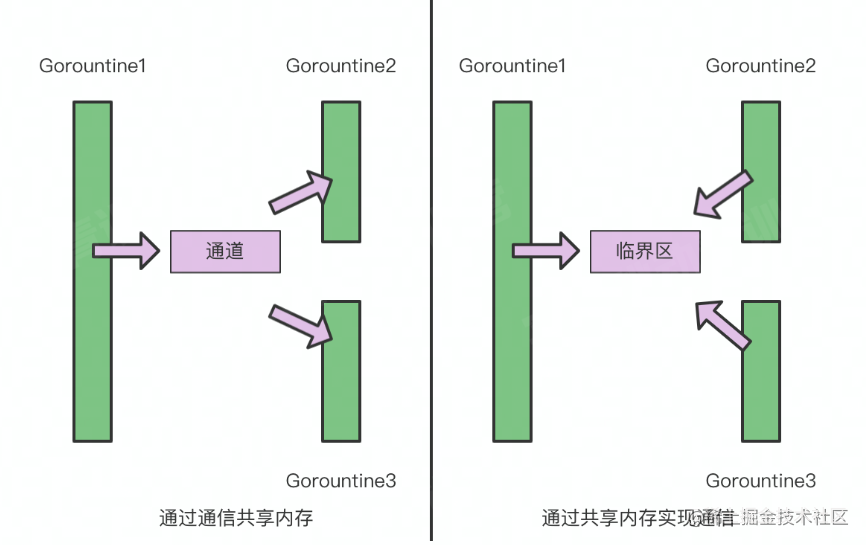

Go advocates sharing memory through communication rather than communicating through shared memory.

So how do we communicate? Through channel.

Channel

Syntax: make(chan element_type, [buffer_size])

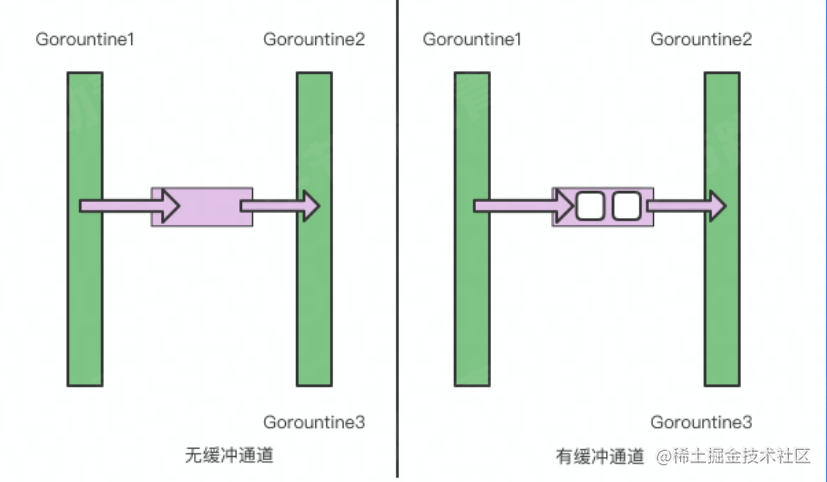

- Unbuffered channel

make(chan int) - Buffered channel

make(chan int, 2)This diagram is very vivid and intuitive~

Here is an example:

- The first goroutine acts as a producer, sending

0~9tosrc - The second goroutine acts as a consumer, computing the square of each number from

srcand sending todest - The main thread outputs each number from

dest

package main

func CalSquare() {

src := make(chan int) // producer

dest := make(chan int, 3) // consumer, buffered to handle fast producer

go func() { // this goroutine sends 0~9 to src

defer close(src) // defer means execute at end of function, used to release allocated resources

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

// <- operator: left side collects data, right side is data to send

src <- i

}

}() // immediately invoked

go func() {

defer close(dest)

for i := range src {

dest <- i * i

}

}()

for i := range dest {

// other complex operations

println(i)

}

}

func main() {

CalSquare()

}You can see that the output is always in order, demonstrating that Go is concurrency-safe.

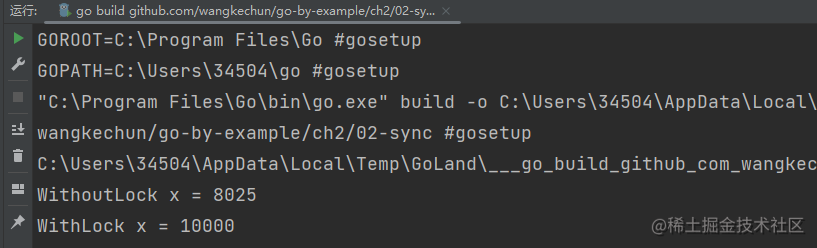

Go also retains the shared memory approach, using sync for synchronization, as follows:

package main

import (

"sync"

"time"

)

var (

x int64

lock sync.Mutex

)

func addWithLock() { // increment x to 2000, using lock is safe

for i := 0; i < 2000; i++ {

lock.Lock() // acquire lock

x += 3

x -= 2

lock.Unlock() // release lock

}

}

func addWithoutLock() { // without lock

for i := 0; i < 2000; i++ {

x += 3

x -= 2

}

}

func Add() {

x = 0

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

go addWithoutLock()

}

time.Sleep(time.Second) // sleep 1s

println("WithoutLock x =", x)

x = 0

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

go addWithLock()

}

time.Sleep(time.Second) // sleep 1s

println("WithLock x =", x)

}

func main() {

Add()

}PS: Tried many times without conflicts, lol. Made the computation slightly more complex and conflicts appeared.

Dependency Management

Any large project development inevitably involves dependency management. Go’s dependency management has evolved through GOPATH -> Go Vendor -> Go Module, and now mainly uses the Go Module approach.

- Different environments depend on different versions, so how do we control dependency library versions?

GOPATH

- Project code directly depends on code under src

- Downloads the latest version of packages to the src directory via

go get

This approach leads to a problem: inability to implement multi-version control (A and B depend on different versions of the same package - out of luck).

Go Vendor

- A new

vendordirectory is added under the project directory, containing copies of all dependency packages - Takes a roundabout approach through vendor => GOPATH

PS: Feels quite similar to frontend’s package.json… dependency issues really are unavoidable.

This created new problems:

- Unable to control dependency versions

- Updating projects may cause dependency conflicts, leading to compilation errors

Go Module

- Manages dependency package versions through

go.modfile - Manages dependency packages through

go get/go modcommand tools

Achieving the ultimate goal: being able to both define version rules and manage project dependency relationships.

Can be compared to Maven in Java.

Dependency Configuration go.mod

Dependency identification syntax: module path + version for unique identification

[Module Path][Version/Pseudo-version]

module example/project/app basic unit of dependency management

go 1.16 standard library

require ( unit dependencies

example/lib1 v1.0.2

example/lib2 v1.0.0 // indirect

example/lib3 v0.1.0-20190725025543-5a5fe074e612

example/lib4 v0.0.0-20180306012644-bacd9c7ef1dd // indirect

example/lib5/v3 v3.0.2

example/lib6 v3.2.0+incompatible

)As shown above, note that:

- Modules with major version 2+ will have a /vN suffix added to the path

- Dependencies with major version 2+ that don’t have a go.mod file will be marked

+incompatibleDependency version rules are divided into semantic versioning and commit-based pseudo-versions.

Semantic Versioning

Format: ${MAJOR}.${MINOR}.${PATCH} V1.3.0, V2.3.0, …

- Different

MAJORversions indicate incompatible APIs- Even for the same library, different MAJOR versions are considered different modules

MINORversions typically add new functions or features, backward compatiblePATCHversions generally fix bugs

Commit-based Versioning

Format: ${vx.0.0-yyyymmddhhmmss-abcdefgh1234}

- The version prefix follows semantic versioning

- Timestamp (

yyyymmddhhmmss), which is the commit time - Checksum (

abcdefgh1234), a 12-character hash prefix- After each

commit, Go generates a pseudo-version number by default

- After each

Mini Quiz

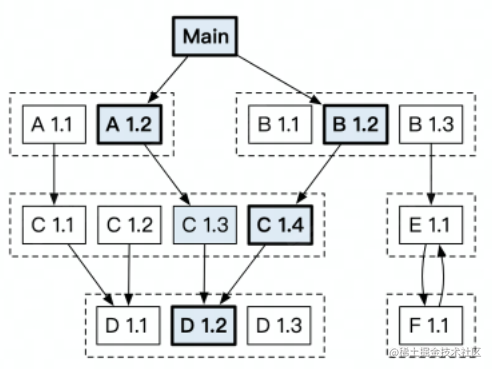

- If project X depends on projects A and B, and A and B respectively depend on versions v1.3 and v1.4 of project C, with the dependency graph as shown above, what version of project C will be used during final compilation ? {.quiz} - v1.3 - v1.4 {.correct} - Use v1.3 when A uses C, use v1.4 when B uses C

{.options} > Answer: B - Select the minimum compatible version \

This is Go’s version selection algorithm - select the minimum compatible version, and v1.4 is backward compatible with v1.3 (semantic versioning). Why not v1.3? Because it’s not forward compatible. If there were also v1.5, it wouldn’t be selected because v1.4 is the minimum compatible version that meets the requirements.

Dependency Distribution

Where do we download these dependencies? That’s dependency distribution.

Download from corresponding repositories on code hosting systems like GitHub?

GitHub is a common code hosting platform, and dependencies defined in Go Modules can ultimately correspond to a specific commit or version of a project in a multi-version code management system.

For dependencies defined in go.mod, you can download specified software dependencies from corresponding repositories to complete dependency distribution.

There are problems though:

- Cannot guarantee build determinism

- Software authors may directly modify software versions, causing the next build to use different dependency versions or fail to find dependency versions

- Cannot guarantee dependency availability

- Software authors may delete software from code platforms, making dependencies unavailable

- Increases pressure on third-party code hosting platforms

These problems are solved through the Proxy approach.

Go Proxy is a service site that caches software content from source sites. Cached software versions won’t change, and remain available even after the source site software is deleted.

After using Go Proxy, dependencies are pulled directly from Go Proxy sites during builds.

Go Modules controls how to use Go Proxy through the GOPROXY environment variable.

Service site URL list, where direct indicates the source: GOPROXY="https://proxy1.cn, https://proxy2.cn,direct"

- GOPROXY is a list of Go Proxy site URLs, where

directcan be used to indicate the source. The overall dependency resolution path will first try to download dependencies fromproxy1. If they don’t exist onproxy1, it proceeds toproxy2. Ifproxy2also doesn’t have them, it falls back to the source site to download dependencies directly, caching them on theproxysite.

Tools

go get example.org/pkg

| Suffix | Meaning |

|---|---|

| @update | Default |

| @none | Remove dependency |

| @v1.1.2 | Tag version, semantic version |

| @23dfdd5 | Specific commit |

| master | Latest commit of branch |

go mod

| Suffix | Meaning |

|---|---|

| init | Initialize, create go.mod file |

| download | Download modules to local cache |

| tidy | Add needed dependencies, remove unneeded ones |

Running go mod tidy before each code commit can reduce the time to build the entire project.

Testing

Testing is generally divided into regression testing, integration testing, and unit testing. From front to back, coverage gradually increases, while cost gradually decreases, so unit test coverage determines code quality to a certain extent.

- Regression testing is generally done by QA engineers manually testing some fixed mainstream process scenarios through the terminal

- Integration testing verifies system functionality dimensions

- Unit testing is done during the development phase, where developers verify the functionality of individual functions and modules

Unit testing mainly includes: input, test unit, output, and verification.

The concept of “unit” is broad, including interfaces, functions, modules, etc. The final verification ensures that the code’s functionality matches our expectations.

Unit testing has the following benefits:

- Quality assurance

- When overall coverage is sufficient, it ensures both correctness of new features and that existing code hasn’t been broken

- Efficiency improvement

- When code has bugs, unit tests can help locate and fix problems within a shorter cycle

Go’s unit testing has the following rules:

- All test files end with

_test.go func TestXxx(testing.T)- Initialization logic goes in the

TestMainfunction (data loading/configuration before tests, resource release after tests, etc.)

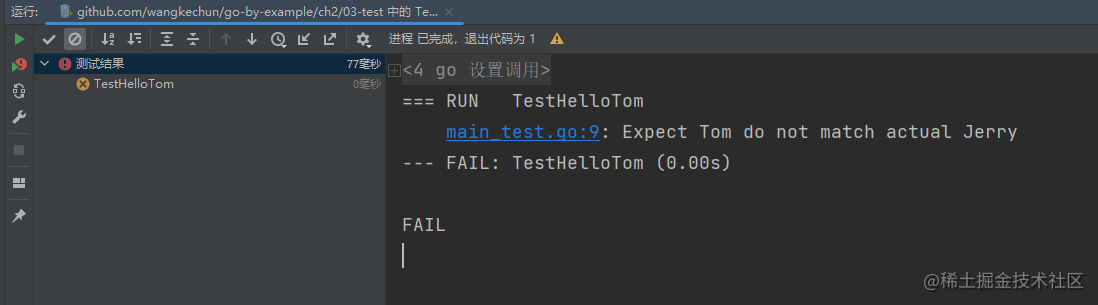

Example: main.go

package main

func HelloTom() string {

return "Jerry"

}main_test.go

package main

import "testing"

func TestHelloTom(t *testing.T) {

output := HelloTom()

expectOutput := "Tom"

if output != expectOutput {

t.Errorf("Expect %s do not match actual %s", expectOutput, output)

}

}

In actual projects, unit test coverage:

- Generally requires 50%~60% coverage

- For critical financial services, coverage may need to reach 80%

Unit tests need to ensure stability and idempotency:

- Stability means mutual isolation - being able to run tests at any time, in any environment

- Idempotency means each test run should produce the same results as before

To achieve this goal, the mock mechanism is used.

bouk/monkey: Monkey patching in Go

monkey is an open-source mock testing library that can mock methods or instance methods through reflection and pointer assignment. Monkey Patch’s scope is at Runtime - during runtime, through Go’s unsafe package, it can replace the address of function A in memory with the address of runtime function B, redirecting the implementation of the function to be stubbed.

Go also provides a benchmark testing framework:

- Benchmark testing refers to testing the runtime performance and CPU consumption of a piece of code.

In actual project development, we often encounter code performance bottleneck issues. To locate problems, we often need to do performance analysis, which is where benchmark testing comes in. The usage is similar to unit testing.

Mentioned

fastrand, address: bytedance/gopkg: Universal Utilities for Go

Summary and Reflections

This lesson mainly covered concurrent management, dependency configuration, and testing in Go. There’s a lot of content that needs thorough digestion. There’s also a project practice session coming up, which I’ll work on tomorrow.

This lesson’s content comes from Teacher Zhao Zheng’s course in the 3rd Youth Training Camp.

喜欢的话,留下你的评论吧~