This article has been machine-translated from Chinese. The translation may contain inaccuracies or awkward phrasing. If in doubt, please refer to the original Chinese version.

The third ByteDance Youth Camp is a backend session, and the course has started. Happily writing notes! The class covered Go’s basic syntax in great detail, and combined with my own reading of “The Go Programming Language,” I’ve compiled this article. It feels like there are many commonalities with JS and C/C++.

Content sourced from: The Go Programming Language and the Third Youth Camp Course Course source code: wangkechun/go-by-example

Introduction to Go and Installation

What is Go?

- High performance, high concurrency

- Rich standard library

- Complete toolchain

- Static linking

- Fast compilation

- Cross-platform

- Garbage collection

In summary, it combines the performance of C/C++ with the simplicity and comprehensive standard library of languages like Python.

Installation

- Visit https://go.dev/, click Download, download the installer for your platform, and install

- If you cannot access the above URL, visit https://studygolang.com/dl to download and install instead

- If accessing GitHub is slow, it’s recommended to configure go mod proxy. Refer to the instructions at https://goproxy.cn/ to significantly speed up downloading third-party dependency packages

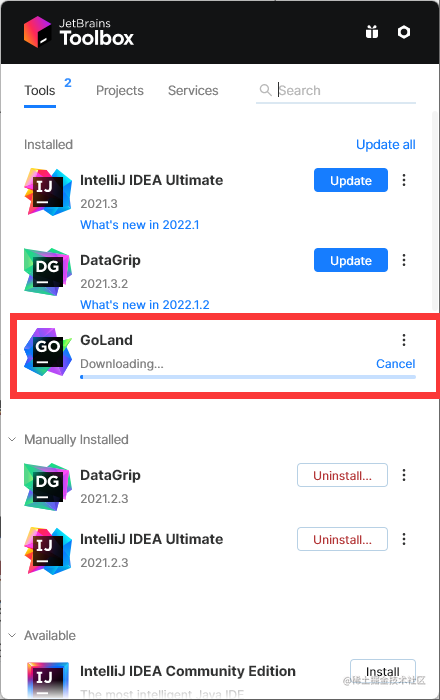

IDE Recommendations

- VSCode with the Go plugin

- GoLand A new IDE from the JetBrains family

You can conveniently experience the course’s sample project through GitHub: Dashboard — Gitpod

Basic Data Types

Integers

Similar to C++, integers are divided into signed and unsigned types. Signed integers:

- int8, int16, int32, and int64

- Corresponding to 8-bit, 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit signed integers

- uint8, uint16, uint32, and uint64 correspond to unsigned integers

- Additionally, there are two types corresponding to the machine word size of the specific CPU platform: signed and unsigned integers

intanduint, both having the same size: 32 or 64 bits- Different compilers may produce different sizes even on the same hardware platform.

- The Unicode character

runetype is equivalent toint32, typically used to represent a Unicode code point. These two names can be used interchangeably. byteis an equivalent type ofuint8. Thebytetype is generally used to emphasize that the value is raw data rather than a small integer.- The

uintptrtype has no specified bit size but is large enough to hold a pointer. It’s only needed in low-level programming, especially where Go interfaces with C language libraries or operating system interfaces. We’ll see similar examples in the unsafe package section of Chapter 13.

You can print numbers in binary format using the %b parameter of the Printf function, and use %d, %o, or %x to control the output base format. This is similar to formatted output in C.

var x uint8 = 1<<1 | 1<<5

fmt.Printf("%08b\n", x) // "00100010", the set {1, 5}

o := 0666

fmt.Printf("%d %[1]o %#[1]o\n", o) // "438 666 0666"

x := int64(0xdeadbeef)

fmt.Printf("%d %[1]x %#[1]x %#[1]X\n", x)

// Output:

// 3735928559 deadbeef 0xdeadbeef 0XDEADBEEF

ascii := 'a'

unicode := '国'

newline := '\n'

fmt.Printf("%d %[1]c %[1]q\n", ascii) // "97 a 'a'"

fmt.Printf("%d %[1]c %[1]q\n", unicode) // "22269 国 '国'"In the examples above, normally when a Printf format string contains multiple % parameters, the same number of additional operands is included. However, the [1] adverb after % tells Printf to reuse the first operand.

- The

#adverb after%tellsPrintfto generate0,0x, or0Xprefixes when outputting with%o,%x, or%X. - Characters are printed using the

%cparameter, or using%qto print characters with single quotes

The built-in len function returns a signed int, which allows reverse loop processing as in the following example:

medals := []string{"gold", "silver", "bronze"}

for i := len(medals) - 1; i >= 0; i-- {

fmt.Println(medals[i]) // "bronze", "silver", "gold"

}Floating Point Numbers

Go has two floating-point types: float32 and float64

Their range limits can be found in the math package.

- The constant

math.MaxFloat32represents the maximum value afloat32can represent, approximately3.4e38; the correspondingmath.MaxFloat64constant is approximately1.8e308. The smallest values they can represent are approximately1.4e-45and4.9e-324respectively. - Using the

%gparameter ofPrintfprints floating-point numbers in a more compact representation with sufficient precision, but for tabular data,%e(with exponent) or%fformat may be more appropriate. All three formats allow specifying print width and controlling print precision.

for x := 0; x < 8; x++ {

fmt.Printf("x = %d e^x = %8.3f\n", x, math.Exp(float64(x)))

}

// x = 0 e^x = 1.000

// x = 1 e^x = 2.718

// x = 2 e^x = 7.389

// x = 3 e^x = 20.086

// x = 4 e^x = 54.598

// x = 5 e^x = 148.413

// x = 6 e^x = 403.429

// x = 7 e^x = 1096.633Besides providing a large number of commonly used mathematical functions, the math package also provides creation and testing of special values defined in the IEEE754 floating-point standard: positive and negative infinity Inf -Inf, used to represent numbers that overflow and the result of division by zero; and NaN (Not a Number), generally used to represent invalid division operations such as 0/0 or Sqrt(-1).

var z float64

fmt.Println(z, -z, 1/z, -1/z, z/z) // "0 -0 +Inf -Inf NaN"- Go’s

NaNis similar to JavaScript’s — it is not equal to any number, including itself. You can usemath.IsNaNto test whether a number is NaN.

nan := math.NaN()

fmt.Println(nan == nan, nan < nan, nan > nan) // "false false false"Complex Numbers

Go provides two precisions of complex number types: complex64 and complex128, corresponding to float32 and float64 floating-point precisions respectively. The built-in complex function is used to construct complex numbers, and the built-in real and imag functions return the real part and imaginary part of a complex number respectively.

var x complex128 = complex(1, 2) // 1+2i

var y complex128 = complex(3, 4) // 3+4i

fmt.Println(x*y) // "(-5+10i)"

fmt.Println(real(x*y)) // "-5"

fmt.Println(imag(x*y)) // "10"If a floating-point literal or a decimal integer literal is followed by i, such as 3.141592i or 2i, it constructs the imaginary part of a complex number, with the real part being 0:

fmt.Println(1i * 1i) // "(-1+0i)", i^2 = -1A complex constant can be added to another regular numeric constant.

fmt.Println(1i * 1i) // "(-1+0i)", i^2 = -1The math/cmplx package provides many functions for complex number processing, such as square root and power functions.

fmt.Println(cmplx.Sqrt(-1)) // "(0+1i)"Boolean

true or false, nothing much to say here.

Strings

Go’s string type string is an immutable string, the same as JS but different from C++.

Immutability means that if two strings share the same underlying data, it’s safe. This makes copying strings of any length inexpensive. Similarly, a string

sand its substring slices[7:]can safely share the same memory. In neither case is it necessary to allocate new memory.

The i-th byte of a string is not necessarily the i-th character of the string, because UTF-8 encoding of non-ASCII characters may require two or more bytes.

s[i:j] generates a new string based on the original string s starting from the i-th byte up to the j-th byte (not including j itself). The new string will contain j-i bytes.

- Both

iandjcan be omitted. When omitted,0is used as the start position andlen(s)as the end position.

fmt.Println(s[0:5]) // "hello"

fmt.Println(s[:5]) // "hello"

fmt.Println(s[7:]) // "world"

fmt.Println(s[:]) // "hello, world"The + operator concatenates two strings to construct a new string:

fmt.Println("goodbye" + s[5:]) // "goodbye, world"String comparison is done byte by byte, and the comparison result follows the natural encoding order of the strings.

Go source files are always encoded in UTF-8, and Go text strings are also processed in UTF-8 encoding, so we can write Unicode code points directly in string literals.

A raw string literal uses backticks instead of double quotes:

const GoUsage = `Go is a tool for managing Go source code.

Usage:

go command [arguments]

...`In raw string literals, there are no escape operations; all content is literal, including backspaces and newlines, so a raw string literal in a program can span multiple lines.

- You cannot directly write a backtick inside a raw string literal (you can use octal or hexadecimal escapes, or concatenate with ”`” string constants).

- The only special processing is removing carriage returns to ensure values are the same across all platforms, including systems that include carriage returns in text files.

Windows systems include both carriage return and newline in text files.

Here are some string methods:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"strings"

)

func main() {

a := "hello"

fmt.Println(strings.Contains(a, "ll")) // true

fmt.Println(strings.Count(a, "l")) // 2

fmt.Println(strings.HasPrefix(a, "he")) // true

fmt.Println(strings.HasSuffix(a, "llo")) // true

fmt.Println(strings.Index(a, "ll")) // 2

fmt.Println(strings.Join([]string{"he", "llo"}, "-")) // he-llo

fmt.Println(strings.Repeat(a, 2)) // hellohello

fmt.Println(strings.Replace(a, "e", "E", -1)) // hEllo

fmt.Println(strings.Split("a-b-c", "-")) // [a b c]

fmt.Println(strings.ToLower(a)) // hello

fmt.Println(strings.ToUpper(a)) // HELLO

fmt.Println(len(a)) // 5

b := "你好"

fmt.Println(len(b)) // 6

}In Go, you can easily use

%vto print any type of variable without distinguishing between numbers and strings. You can also use%+vfor more detailed results, and%#vfor even more detail.

package main

import "fmt"

type point struct {

x, y int

}

func main() {

s := "hello"

n := 123

p := point{1, 2}

fmt.Println(s, n) // hello 123

fmt.Println(p) // {1 2}

fmt.Printf("s=%v\n", s) // s=hello

fmt.Printf("n=%v\n", n) // n=123

fmt.Printf("p=%v\n", p) // p={1 2}

fmt.Printf("p=%+v\n", p) // p={x:1 y:2}

fmt.Printf("p=%#v\n", p) // p=main.point{x:1, y:2}

f := 3.141592653

fmt.Println(f) // 3.141592653

fmt.Printf("%.2f\n", f) // 3.14

}String and Number Conversion

In Go, conversions between strings and numeric types are all in the strconv package, which is an abbreviation of “string convert.” You can use ParseInt or ParseFloat to parse a string. You can also use Atoi to convert a decimal string to a number, and Itoa to convert a number to a string.

- If the input is invalid, all these functions return an error except Itoa

package main

import (

"fmt"

"strconv"

)

func main() {

f, _ := strconv.ParseFloat("1.234", 64)

fmt.Println(f) // 1.234

n, _ := strconv.ParseInt("111", 10, 64)

fmt.Println(n) // 111

n, _ = strconv.ParseInt("0x1000", 0, 64)

fmt.Println(n) // 4096

n2, _ := strconv.Atoi("123")

fmt.Println(n2) // 123

n2, err := strconv.Atoi("AAA")

fmt.Println(n2, err) // 0 strconv.Atoi: parsing "AAA": invalid syntax

n3 := strconv.Itoa(123) // This doesn't return an error

fmt.Println(n3) // 123

}Constants

Like constants in other languages, the value of a constant cannot be modified and must be initialized. When declaring constants in batch, the initialization expression can be omitted for all except the first one. If omitted, the previous constant’s initialization expression is used:

const pi = 3.14159 // approximately; math.Pi is a better approximation

const (

e = 2.71828182845904523536028747135266249775724709369995957496696763

pi = 3.14159265358979323846264338327950288419716939937510582097494459

)

const (

a = 1

b

c = 2

d

)The iota Constant Generator

Similar to C/C++ enum types!

Constant declarations can use the iota constant generator for initialization. It’s used to generate a set of constants initialized with similar rules, without having to write the initialization expression for each line. In a const declaration, iota is set to 0 on the line of the first declared constant, then incremented by one on each subsequent line with a constant declaration.

type Weekday int

const (

Sunday Weekday = iota

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

)

// Sunday corresponds to 0

// Monday corresponds to 1

// ....

// Saturday corresponds to 6It can also be used with complex expressions, like the following example where each constant corresponds to the expression 1 << iota, which produces consecutive powers of 2:

type Flags uint

const (

FlagUp Flags = 1 << iota // is up

FlagBroadcast // supports broadcast access capability

FlagLoopback // is a loopback interface

FlagPointToPoint // belongs to a point-to-point link

FlagMulticast // supports multicast access capability

)

fmt.Println(FlagUp, FlagBroadcast, FlagLoopback, FlagPointToPoint, FlagMulticast)

// 1 2 4 8 16Untyped Constants

Many constants don’t have a specific underlying type. Go’s compiler provides higher-precision arithmetic for numeric constants without a specific underlying type than for underlying types; you can assume at least 256 bits of arithmetic precision. There are six kinds of untyped constants: untyped boolean, untyped integer, untyped character, untyped floating-point, untyped complex, and untyped string.

Only constants can be untyped. When an untyped constant is assigned to a variable, the untyped constant is implicitly converted to the corresponding type, if the conversion is legal.

- For variable declarations without an explicit type (including short variable declarations), the form of the constant will implicitly determine the variable’s default type.

- Untyped integer constants convert to

int, whose memory size is uncertain, while untyped floating-point and complex constants convert to memory-size-definedfloat64andcomplex128.

- Untyped integer constants convert to

Program Structure

Declarations and Variables

var

The general syntax is:

var variableName type = expressionIf the type is omitted, it’s automatically inferred from the expression. If the expression is empty, the variable is initialized with the zero value (therefore in Go, there are no uninitialized variables).

| Type | Zero Value |

|---|---|

| Numeric | 0 |

| Boolean | false |

| String | "" |

| Aggregate types (arrays, etc) | nil |

You can declare a group of variables in a single declaration statement, or declare and initialize a group of variables using a set of initialization expressions:

var i, j, k int // int int int

var b, f, s = true, 2.3, "hello" // bool float64 stringA group of variables can also be initialized by the multiple return values from a function call:

var f, err = os.Open(name) // os.Open returns a file and an errorShort Variable Declaration :=

In the form name := expression, the variable’s type is automatically inferred from the expression.

- Due to its concise and flexible nature, short variable declarations are widely used for the declaration and initialization of most local variables.

- The

varform is typically used where an explicit variable type needs to be specified, or where the variable will be reassigned later and the initial value is irrelevant.

i := 100 // int

i, j := 0, 1 // int int

var boiling float64 = 100 // a float64

var names []string

var err error- A short variable declaration on a variable already declared in the same lexical scope only performs assignment.

- If the variable was declared in an outer lexical scope, the short variable declaration will redeclare a new variable in the current lexical scope.

Pointers

Similar to C, the & operator takes an address, and * dereferences a pointer.

x := 1

p := &x // p, of type *int, points to x

fmt.Println(*p) // "1"

*p = 2 // equivalent to x = 2

fmt.Println(x) // "2"The zero value of a pointer of any type is nil.

- If

ppoints to a valid variable,p != niltests as true. - Two pointers are equal only when they point to the same variable or both are

nil.

The new Function

new(T) creates an anonymous variable of type T, initializes it to the zero value of type T, and returns the variable’s address. The returned pointer type is *T.

- Go’s

newis a predefined function, not a keyword! So it can be redefined.

p := new(int) // p, *int type, points to an anonymous int variable

fmt.Println(*p) // "0"

*p = 2 // set the anonymous int variable to 2

fmt.Println(*p) // "2"Increment/Decrement

The increment statement i++ adds 1 to i; this is equivalent to i += 1 and i = i + 1. Similarly, i-- subtracts 1 from i. They are statements, not expressions as in other C-family languages.

- Therefore

j = i++is illegal, and ++ and — can only be placed after the variable name, so--iis also illegal.

Type type

Similar to an enhanced version of C++‘s typeof:

type typeName underlyingTypeFor example, two types are declared: Celsius and Fahrenheit corresponding to different temperature units.

- The underlying data type determines its internal structure and representation

- Although they have the same underlying type

float64, they are different data types, so they cannot be compared or combined in an expression. - Type conversion doesn’t change the value itself, but changes its semantics.

import "fmt"

type Celsius float64 // Celsius temperature

type Fahrenheit float64 // Fahrenheit temperature

const (

AbsoluteZeroC Celsius = -273.15 // absolute zero

FreezingC Celsius = 0 // freezing point

BoilingC Celsius = 100 // boiling point

)

func CToF(c Celsius) Fahrenheit { return Fahrenheit(c*9/5 + 32) }

func FToC(f Fahrenheit) Celsius { return Celsius((f - 32) * 5 / 9) }Comparison operators == and < can also be used to compare a named type variable with another variable of the same type, or with an unnamed type value of the same underlying type. However, if two values have different types, they cannot be compared directly:

var c Celsius

var f Fahrenheit

fmt.Println(c == 0) // "true"

fmt.Println(f >= 0) // "true"

fmt.Println(c == f) // compile error: type mismatch

fmt.Println(c == Celsius(f)) // "true"! type conversion doesn't change the valueNamed types can also define new behaviors for values of that type. These behaviors are expressed as a set of functions associated with the type, called the type’s method set (covered in detail in Chapter 6).

In the following declaration, the Celsius type parameter c appears before the function name, indicating that a method named String is declared for the Celsius type. This method returns a string of the type object c with the temperature unit:

func (c Celsius) String() string { return fmt.Sprintf("%g°C", c) }Many types define a String method because when using fmt’s print methods, the String method of the corresponding type is used preferentially:

c := FToC(212.0)

fmt.Println(c.String()) // "100°C"

fmt.Printf("%v\n", c) // "100°C"; no need to call String explicitly

fmt.Printf("%s\n", c) // "100°C"

fmt.Println(c) // "100°C"

fmt.Printf("%g\n", c) // "100"; does not call String

fmt.Println(float64(c)) // "100"; does not call StringLoops for

Command-Line Arguments - The Go Programming Language

Go only has one loop construct: the for loop. There is no while or do while.

The syntax is:

for initialization; condition; post {

// zero or more statements

}The three parts of the for loop don’t need parentheses. Braces are mandatory, and the opening brace must be on the same line as the post statement.

- The

initializationstatement is optional and executed before the loop begins. If present, it must be a simple statement, i.e., a short variable declaration, increment statement, assignment statement, or function call. conditionis a boolean expression whose value is evaluated at the beginning of each loop iteration. Iftrue, the loop body executes.- The

poststatement executes after each loop body execution, thenconditionis re-evaluated. Whenconditionisfalse, the loop ends.

All three parts of the for loop can be omitted. If initialization and post are omitted, it becomes a while loop (semicolons can also be omitted). If all three parts are omitted, it’s an infinite loop that can be broken with break:

i := 1

for {

fmt.Println("loop")

break

}

for j := 7; j < 9; j++ {

fmt.Println(j)

}

for n := 0; n < 5; n++ {

if n%2 == 0 {

continue

}

fmt.Println(n)

}

for i <= 3 {

fmt.Println(i)

i = i + 1

}Branching Structures

if else

Go’s if is similar to Python — no parentheses, but braces are required:

if 7%2 == 0 {

fmt.Println("7 is even")

} else {

fmt.Println("7 is odd")

}

if 8%4 == 0 {

fmt.Println("8 is divisible by 4")

}

if num := 9; num < 0 {

fmt.Println(num, "is negative")

} else if num < 10 {

fmt.Println(num, "has 1 digit")

} else {

fmt.Println(num, "has multiple digits")

}switch

Go’s switch branching structure is similar to C++, but with many differences:

- The variable after switch doesn’t need parentheses

- In C++, if you don’t add

breakto a switch case, it will fall through all subsequent cases. In Go,breakis not needed - Go’s switch is more powerful and can use any variable type, and can even replace arbitrary if-else statements

You can omit the variable after switch and write conditional branches in the cases. This makes the code logic clearer compared to using multiple if-else statements.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

a := 2

switch a {

case 1:

fmt.Println("one")

case 2:

fmt.Println("two")

case 3:

fmt.Println("three")

case 4, 5:

fmt.Println("four or five")

default:

fmt.Println("other")

}

t := time.Now()

switch {

case t.Hour() < 12:

fmt.Println("It's before noon")

default:

fmt.Println("It's after noon")

}

}Process Information

In Go, we can use os.Args to get the command-line arguments specified when the program runs. For example, if we compile a binary file command and run it with abcd, os.Args will be a slice of length 5, where the first element is the name of the binary itself. We can use os.Getenv to read environment variables, and exec to run commands.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"os/exec"

)

func main() {

// go run example/20-env/main.go a b c d

fmt.Println(os.Args) // [/var/folders/8p/n34xxfnx38dg8bv_x8l62t_m0000gn/T/go-build3406981276/b001/exe/main a b c d]

fmt.Println(os.Getenv("PATH")) // /usr/local/go/bin...

fmt.Println(os.Setenv("AA", "BB"))

buf, err := exec.Command("grep", "127.0.0.1", "/etc/hosts").CombinedOutput()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(string(buf)) // 127.0.0.1 localhost

}Composite Data Types

Arrays

An array is a sequence of fixed-length elements of a specific type. An array can have zero or more elements. Because arrays have a fixed length, they are rarely used directly in Go. The type corresponding to arrays is Slice, which is a dynamic sequence that can grow and shrink. Slices are more flexible, but understanding how slices work requires first understanding arrays.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var a [5]int

a[4] = 100

fmt.Println("get:", a[2])

fmt.Println("len:", len(a))

b := [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

fmt.Println(b)

var twoD [2][3]int

for i := 0; i < 2; i++ {

for j := 0; j < 3; j++ {

twoD[i][j] = i + j

}

}

fmt.Println("2d: ", twoD)

}Slices

Slices differ from arrays in that their length can be changed freely, and they support more operations.

- Use

maketo create a slice, and you can access values like arrays - Use

appendto add elements. Note thatappendworks similarly to JavaScript’sconcat— it returns a new array, and you assign the result ofappendback to the original array. - A slice can be initialized with a dynamic length.

len(s) - Slices support Python-like slicing operations, e.g.,

s[2:5]extracts elements from position 2 to 5, not including position 5. However, unlike Python, negative indexing is not supported here

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

s := make([]string, 3)

s[0] = "a"

s[1] = "b"

s[2] = "c"

fmt.Println("get:", s[2]) // c

fmt.Println("len:", len(s)) // 3

s = append(s, "d")

s = append(s, "e", "f")

fmt.Println(s) // [a b c d e f]

c := make([]string, len(s))

copy(c, s)

fmt.Println(c) // [a b c d e f]

fmt.Println(s[2:5]) // [c d e]

fmt.Println(s[:5]) // [a b c d e]

fmt.Println(s[2:]) // [c d e f]

good := []string{"g", "o", "o", "d"}

fmt.Println(good) // [g o o d]

}Map

map is the most frequently used data structure in practice.

- You can use

maketo create an emptymap, which requires two types: thekeytype and thevaluetypemap[string]intmeans thekeytype isstringand thevaluetype isint

- Getting and inserting values in a

mapis similar to C++ STL’s map, done directly viam[key]andm[key] = value - You can use

deleteto remove key-value pairs - Go’s

mapis completely unordered. When iterating, it doesn’t follow alphabetical order or insertion order, but rather random order

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

m := make(map[string]int)

m["one"] = 1

m["two"] = 2

fmt.Println(m) // map[one:1 two:2]

fmt.Println(len(m)) // 2

fmt.Println(m["one"]) // 1

fmt.Println(m["unknow"]) // 0

r, ok := m["unknow"]

fmt.Println(r, ok) // 0 false

delete(m, "one")

m2 := map[string]int{"one": 1, "two": 2}

var m3 = map[string]int{"one": 1, "two": 2}

fmt.Println(m2, m3)

}range

For a slice or a map, we can use range for quick iteration, making the code more concise. When iterating with range over arrays, it returns two values: the first is the index, and the second is the value at that position. If we don’t need the index, we can use underscore _ to ignore it.

Go doesn’t allow unused local variables, as this would cause a compilation error. Use the

blank identifier_(underscore). The blank identifier can be used whenever syntax requires a variable name but program logic doesn’t (such as discarding unnecessary loop indices while retaining element values).

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

nums := []int{2, 3, 4}

sum := 0

for i, num := range nums {

sum += num

if num == 2 {

fmt.Println("index:", i, "num:", num) // index: 0 num: 2

}

}

fmt.Println(sum) // 9

m := map[string]string{"a": "A", "b": "B"}

for k, v := range m {

fmt.Println(k, v) // b 8; a A

}

for k := range m {

fmt.Println("key: ", k) // key: a; key: b

}

for _, v := range m {

fmt.Println("value:", v) // value: A; value: B

}

}Structs

Structs are collections of typed fields. For example, the user struct here contains two fields: name and password.

- You can use the struct name to initialize a struct variable. When constructing, you need to provide initial values for each field

- You can also use key-value pairs to specify initial values, which allows initializing only some fields

- Structs also support pointers, enabling direct modification of structs, which can avoid copying overhead for large structs in some cases

package main

import "fmt"

type user struct {

name string

password string

}

func main() {

a := user{name: "wang", password: "1024"}

b := user{"wang", "1024"}

c := user{name: "wang"}

c.password = "1024"

var d user

d.name = "wang"

d.password = "1024"

fmt.Println(a, b, c, d) // {wang 1024} {wang 1024} {wang 1024} {wang 1024}

fmt.Println(checkPassword(a, "haha")) // false

fmt.Println(checkPassword2(&a, "haha")) // false

}

func checkPassword(u user, password string) bool {

return u.password == password

}

func checkPassword2(u *user, password string) bool {

return u.password == password

}JSON

JSON operations in Go are very straightforward.

- For an existing struct, as long as the first letter of each field is uppercase (i.e., it’s a public field), the struct can be serialized using

json.Marshalto produce a JSON string.

json.Marshalreturns the serialized value and an error, as shown below.

By default, the serialized string has fields starting with uppercase letters. You can use json tags to modify the field names in the output JSON.

- After serialization, the string can be deserialized back into an empty variable using

json.Unmarshal.

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

)

type userInfo struct {

Name string

Age int `json:"age"`

Hobby []string

}

func main() {

a := userInfo{Name: "wang", Age: 18, Hobby: []string{"Golang", "TypeScript"}}

buf, err := json.Marshal(a)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(buf) // [123 34 78 97...]

fmt.Println(string(buf)) // {"Name":"wang","age":18,"Hobby":["Golang","TypeScript"]}

buf, err = json.MarshalIndent(a, "", "\t")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(string(buf))

var b userInfo

err = json.Unmarshal(buf, &b)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Printf("%#v\n", b) // main.userInfo{Name:"wang", Age:18, Hobby:[]string{"Golang", "TypeScript"}}

}Time Handling

The most commonly used function in Go is time.Now() to get the current time. You can also use time.Date to construct a time with a timezone. There are many methods to get the year, month, day, hour, minute, and second of a time point.

- You can use the

Submethod to subtract two times, getting a duration. - The duration can then yield how many hours, minutes, or seconds it contains.

- When interacting with some systems, we often use timestamps. You can use

.Unixto get timestamps.time.Formatandtime.Parseare also available.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

now := time.Now()

fmt.Println(now) // 2022-05-07 13:12:03.7190528 +0800 CST m=+0.004990401

t := time.Date(2022, 5, 7, 13, 25, 36, 0, time.UTC)

t2 := time.Date(2022, 8, 12, 12, 30, 36, 0, time.UTC)

fmt.Println(t) // 2022-05-07 13:25:36 +0000 UTC

fmt.Println(t.Year(), t.Month(), t.Day(), t.Hour(), t.Minute()) // 2022 March 27 1 25

fmt.Println(t.Format("2006-01-02 15:04:05")) // 2022-05-07 13:25:36

diff := t2.Sub(t)

fmt.Println(diff) // 2327h5m0s

fmt.Println(diff.Minutes(), diff.Seconds()) // 139625 8.3775e+06

t3, err := time.Parse("2006-01-02 15:04:05", "2022-05-07 13:25:36")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(t3 == t) // true

fmt.Println(now.Unix()) // 1651900531

}

Functions

Unlike many other languages, Go places function parameter types after the variable names. Go natively supports returning multiple values from functions.

- In real business logic code, almost all functions return two values: the first is the return value, and the second is an error message. As shown in the

existsexample below.

package main

import "fmt"

func add(a int, b int) int {

return a + b

}

func add2(a, b int) int {

return a + b

}

func exists(m map[string]string, k string) (v string, ok bool) {

v, ok = m[k]

return v, ok

}

func main() {

res := add(1, 2)

fmt.Println(res) // 3

v, ok := exists(map[string]string{"a": "A"}, "a")

fmt.Println(v, ok) // A True

}Error Handling

Error handling in Go uses a separate return value to convey error information.

- Adding an

errorafter the function return type indicates that the function may return an error. When implementing the function,returnneeds to simultaneously return two values. - When an error occurs, you can

return niland anerror. If there’s no error, return the original result andnil.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

type user struct {

name string

password string

}

func findUser(users []user, name string) (v *user, err error) {

for _, u := range users {

if u.name == name {

return &u, nil

}

}

return nil, errors.New("not found")

}

func main() {

u, err := findUser([]user{{"wang", "1024"}}, "wang")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

fmt.Println(u.name) // wang

if u, err := findUser([]user{{"wang", "1024"}}, "li"); err != nil {

fmt.Println(err) // not found

return

} else {

fmt.Println(u.name)

}

}Tool Recommendations

Several code generation tools mentioned in class:

Exercises

- Modify the final code of the first guessing game example, using

fmt.Scanfto simplify the code implementation

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math/rand"

"time"

)

func main() {

maxNum := 100

rand.Seed(time.Now().UnixNano())

secretNumber := rand.Intn(maxNum)

// fmt.Println("The secret number is ", secretNumber)

fmt.Println("Please input your guess")

//reader := bufio.NewReader(os.Stdin)

for {

//input, err := reader.ReadString('\n')

var guess int

_, err := fmt.Scanf("%d", &guess)

fmt.Scanf("%*c") // consume newline

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("An error occured while reading input. Please try again", err)

continue

}

//input = strings.TrimSuffix(input, "\n")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Invalid input. Please enter an integer value")

continue

}

fmt.Println("You guess is", guess)

if guess > secretNumber {

fmt.Println("Your guess is bigger than the secret number. Please try again")

} else if guess < secretNumber {

fmt.Println("Your guess is smaller than the secret number. Please try again")

} else {

fmt.Println("Correct, you Legend!")

break

}

}

}-

Modify the final code of the second command-line dictionary example, adding support for another translation engine

-

Based on the previous step, modify the code to implement parallel requests to two translation engines to improve response speed

Summary and Reflections

The class covered Go’s basic syntax in great detail, and combined with my own reading of “The Go Programming Language,” I’ve compiled this article. It feels like there are many commonalities with JS and C/C++.

Content sourced from: The Go Programming Language and the Third Youth Camp Course

喜欢的话,留下你的评论吧~