This article has been machine-translated from Chinese. The translation may contain inaccuracies or awkward phrasing. If in doubt, please refer to the original Chinese version.

I. Fibonacci Game

Description

The basic Fibonacci Game is described as follows:

There is a pile of stones. Two extremely intelligent players play a game. The first player can take any number of stones but cannot take all of them. After that, each player can take at least 1 stone and at most 2 times the number of stones the opponent just took. The player who takes the last stone wins. Find the losing position.

Conclusion

The first player loses if and only if the total number of stones is a Fibonacci number.

Proof

The proof is as follows, reposted from this proof Using the Zeckendorf Theorem: Any positive integer can be represented as the sum of several non-consecutive Fibonacci numbers.

II. Bash Game

Description

The basic Bash Game is described as follows:

There is a pile of n items. Two players take turns removing items. Each player must take at least one and at most m items per turn. The player who takes the last item wins.

Conclusion

If n % (m+1) == 0, the first player loses.

bool FirstWin(int n, int m) { //returns true if first player wins

return n % (m+1) != 0;

}Proof

The game proceeds as follows: Proof Here is a brief explanation: Congruence theorem: If n % (m+1) = r, and the first player takes r items, then no matter how many items (1 to m) the second player takes, the first player can always take enough to make a total of (m+1), so the first player wins. Otherwise, the first player loses. When n < m, the first player can take everything in one turn and also wins.

Bash Game Variant

There is a pile of n items. Two players take turns removing items. Each player must take at least p and at most q items per turn. If fewer than p items remain, they are all taken at once. The player who takes the last item wins.

If n % (p+q) = r, then when r != 0 && r < p, the first player wins; otherwise, the first player loses.

III. Wythoff Game

Description

The basic Wythoff Game is described as follows:

There are two piles with some items each. Two players take turns removing items from one pile or the same number of items from both piles. Each player must take at least one item, with no upper limit. The player who takes the last item wins.

Conclusion

Let the two piles have a and b items respectively. Calculate the difference between a and b, multiply by the golden ratio, and check if the result equals the minimum of a and b. If it does, the first player loses.

bool FirstWin(int a, int b) { //returns true if first player wins

double G = (sqrt(5.0)+1) / 2; //golden ratio

int t = abs(a-b) * G;

return d != min(a,b);

}Proof

The proof is quite complex… saving the template for now, see Proof

IV. Nim Game

Description

The basic Nim Game is described as follows:

There are several piles with various numbers of items. Two players take turns removing any number of items from one pile. Each player must take at least one item, with no upper limit. The player who takes the last item wins.

Conclusion

XOR all N pile counts together. If the result is 0, the first player loses; otherwise, the first player wins.

bool FirstWin(int a, int b) { //returns true if first player wins

int ans = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < N; ++i) ans ^= a[i];//a[i] is the item count

return ans != 0;

}Proof

The proof is also quite complex… see Proof The SG function will be introduced later. Generally, the SG value of the terminal position is set to 0. SG Theorem: The SG value of the sum of games is the XOR of the SG values of each sub-game. With the above conclusion, we realize that a Nim game can actually be decomposed into n Bash games. If a Bash game allows unlimited moves, then using the remaining stone count as the state, SG(x) = x. So the answer to this problem is the XOR of all pile sizes. If the value is 0, the first player loses; otherwise, the first player can always make a move that results in an XOR value of 0 for the next position, and the second player loses.

Variants

Reference blog: Nim Game and Its Variants

Anti-Nim Game

Anti-Nim game, as the name suggests:

There are several piles with various numbers of items. Two players take turns removing any number of items from one pile. Each player must take at least one item, with no upper limit. The player who takes the last item loses.

Example Problem E - Misere Nim The first player wins in only two cases: 1) all piles have exactly 1 stone and the XOR sum is 0, or 2) there exists a pile with more than 1 stone and the XOR sum is not 0.

V. SG Function

Reference blogs: SG Function, Combinatorial Games - SG Function and SG Theorem

1. Concept Introduction

ICG (Impartial Combinatorial Game)

The conditions are as follows: Problems typically describe a game between two players A and B.

- A and B alternate turns.

- Each turn, the player can choose any operation from the set of legal operations.

- For any possible game state, the set of legal operations depends only on the state itself, not on other factors (independent of the player or previous operations).

- If the current player cannot make a legal move, they lose.

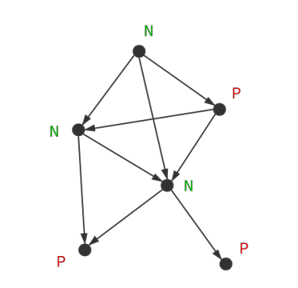

Using the Bash game described above as an example: there is a pile of n items, two players take turns removing items, each player must take at least one and at most m items per turn, and the player who takes the last item wins. A fair game can be abstractly represented as a directed acyclic graph, where each node corresponds to a state and each directed edge represents a legal transition from one state to another.

Winning and Losing Positions

- Losing position (P-position): The previous player (the one who just moved) is in a winning position. Whoever faces this state will lose.

- Winning position (N-position): The next player (the one about to move) is in a winning position. Whoever faces this state will win.

Properties:

- All terminal positions are losing positions.

- From any winning position, there is at least one move that leads to a losing position.

- From a losing position, every possible move leads to a winning position.

2. SG Function

Definition of the mex Operation

First, define the mex (minimal excludant) operation, which is applied to a set and returns the smallest non-negative integer not in the set.

- For example, mex{2,3,5}=0, mex{0,1,2,4}=3, mex{}=0.

For any state x, define SG(x) = mex(S), where S is the set of SG function values of x’s successor states. For example, if x has three successor states a, b, and c, then SG(x) = mex{SG(a), SG(b), SG(c)}. Thus, the terminal state of set S is necessarily the empty set, so SG(x) = 0 if and only if x is a losing position P.

Through the SG function, every ICG can be converted into a Nim game. The domain of the SG function is all nodes on the ICG’s decision tree. Specifically: SG(x) = mex{SG(y) | y is a successor of x}. For a node u on the ICG’s decision tree, we can think of it as a Nim game with only one pile of SG(u) stones. I understood how to compute the SG function through this blog: Combinatorial Games - SG Function and SG Theorem.

Stone-taking Problem There is 1 pile of n stones. Each turn, you can only take { 1, 3, 4 } stones. The player who takes the last stone wins. What are the SG values for each number?

SG[0]=0, f[]={1,3,4},

- x=1: Can take 1 - f{1} stones, leaving {0}, so SG[1] = mex{ SG[0] } = mex{0} = 1;

- x=2: Can take 2 - f{1} stones, leaving {1}, so SG[2] = mex{ SG[1] } = mex{1} = 0;

- x=3: Can take 3 - f{1,3} stones, leaving {2,0}, so SG[3] = mex{SG[2],SG[0]} = mex{0,0} = 1;

- x=4: Can take 4 - f{1,3,4} stones, leaving {3,1,0}, so SG[4] = mex{SG[3],SG[1],SG[0]} = mex{1,1,0} = 2;

- x=5: Can take 5 - f{1,3,4} stones, leaving {4,2,1}, so SG[5] = mex{SG[4],SG[2],SG[1]} = mex{2,0,1} = 3;

And so on… x = 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 … SG[x] = 0 1 0 1 2 3 2 0 …

From the above example, we can derive the steps for computing SG function values. The steps for computing SG values from 1 to n are:

- Use an array f to record the ways to change the current state.

- Use another array to mark the successor states of the current state x.

- Finally, simulate the mex operation: search for the smallest unmarked value among the marked values and assign it to SG(x).

- Repeat steps 2-3 to complete computing values from 1 to n. Template as follows:

//f[N]: ways to change the current state, N is the number of types, f[N] must be preprocessed before getSG

//SG[]: SG function values from 0 to n

//S[]: the set of successor states of x

int f[N],SG[MAXN],S[MAXN];

void getSG(int n){

int i,j;

memset(SG,0,sizeof(SG));

//Since SG[0] is always 0, i starts from 1

for(i = 1; i <= n; i++){

//Reset the successor set for each state

memset(S,0,sizeof(S));

for(j = 0; f[j] <= i && j <= N; j++)

S[SG[i-f[j]]] = 1; //Mark the SG function values of successor states

for(j = 0;; j++) if(!S[j]){ //Find the smallest non-zero value among successor state SG values

SG[i] = j;

break;

}

}

}3. SG Theorem

- The SG function of the sum of games is the XOR of the SG functions of all independent sub-games.

- Therefore, the first player wins if and only if the XOR of the SG function values of all piles is non-zero.

VI. Green Hackenbush (Edge-deletion Game on Trees)

I got stuck on the very first problem, and after looking up the solution, I found it was about a Green Hackenbush game I hadn’t learned. Reference blog: Game Theory - Green Hackenbush. The following content is from that source.

1. Hackenbush Game Overview

The Hackenbush game involves removing edges from a rooted graph until there are no edges connected to the ground. The ground is represented by a dashed line. When removing an edge, all edges above it that are connected only through that edge are also removed, similar to cutting a tree branch — everything above the cut also falls. Here, we discuss the impartial version of this game, where each player can delete any edge on their turn. This version is called Green Hackenbush, where every edge is green, abbreviated as GH game below. There is also a partisan version called Blue-Red Hackenbush, where some edges are blue and some are red — player one can only delete blue edges and player two can only delete red edges. In general, a Hackenbush game may have blue edges (only for player one), red edges (only for player two), and green edges (available to both players).

2. Colon Principle

For a node on a tree, its branches can be transformed into a single bamboo stalk rooted at that node, where the length of the bamboo equals the XOR of the edge counts of its branches.

If all edge weights are 1, it is a basic Green Hackenbush game: the SG function of each node = XOR of (SG function of child nodes + 1). When weights differ: when edge weight AB = 1, SG[A] = SG[B] + 1. When edge weight AB is even, SG[A] = SG[B]. When edge weight AB is odd, SG[A] = SG[B] ^ 1.

喜欢的话,留下你的评论吧~