This article has been machine-translated from Chinese. The translation may contain inaccuracies or awkward phrasing. If in doubt, please refer to the original Chinese version.

An interactive, high-quality performance optimization blog post recommended by antfu. The author has 20 years of experience, with genuinely detailed insights. I've attempted to translate it with some of my own polishing. I strongly recommend reading the original English version to experience the interactive elements -- here I'll use screenshots as substitutes. This is my first translation; corrections are welcome! This translated blog post link: https://ysx.cosine.ren/optimizing-javascript-translate Original link: https://romgrk.com/posts/optimizing-javascript

Original author: romgrk

I often feel that typical JavaScript code runs much slower than it could, simply because it hasn't been properly optimized. Below is a summary of common optimization techniques I've found useful. Note that the tradeoff between performance and readability often favors readability, so I'll leave it to the reader to decide when to choose performance versus readability. I also want to say that discussing optimization necessarily requires talking about benchmarking. If a function initially accounts for only a small fraction of the total runtime, spending hours micro-optimizing it to run 100x faster is pointless. The most important first step in optimization is benchmarking, which I'll cover later. Also note that microbenchmarks are often flawed, and the ones presented here may be no exception. I've tried to avoid these pitfalls, but don't blindly apply any of the points presented here without benchmarking.

I've provided runnable examples for all possible cases. They show the results I obtained on my machine (Brave 122 on Arch Linux) by default, but you can run them yourself. Although I hate to say it, Firefox has fallen a bit behind in the optimization game and currently accounts for only a small share of traffic, so I wouldn't recommend using Firefox results as useful indicators.

0. Avoid Unnecessary Work

This may sound obvious, but it needs to be here because there can be no other first step to optimization: if you're trying to optimize, you should first consider avoiding unnecessary work. This encompasses concepts such as memoization, laziness, and incremental computation. The specific application varies depending on context. For example, in React, this means applying memo(), useMemo(), and other applicable primitives.

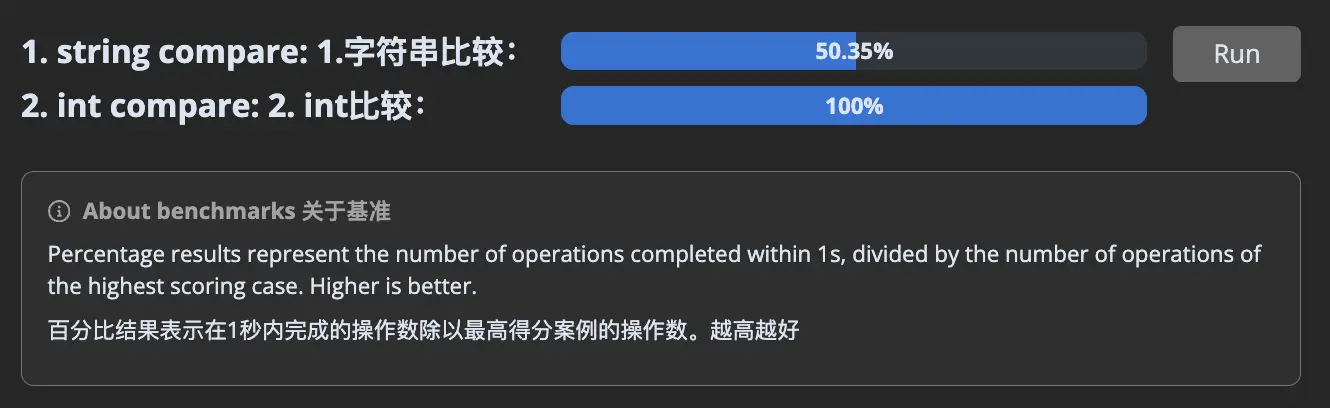

1. Avoid String Comparisons

JavaScript easily hides the true cost of string comparisons. If you needed to compare strings in C, you'd use the strcmp(a, b) function. JavaScript uses === for comparison, so you don't see strcmp. But it's there. strcmp typically (but not always) needs to compare each character of one string with the characters of another; string comparison has a time complexity of O(n). A common JavaScript pattern to avoid is using strings as enums. However, with the advent of TypeScript, this should be easy to avoid since enum types default to integers.

// No

enum Position {

TOP = 'TOP',

BOTTOM = 'BOTTOM',

}

// Yeppers

enum Position {

TOP, // = 0

BOTTOM, // = 1

}Here's a cost comparison:

// 1. string compare

const Position = {

TOP: 'TOP',

BOTTOM: 'BOTTOM',

};

let _ = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

let current = i % 2 === 0 ? Position.TOP : Position.BOTTOM;

if (current === Position.TOP) _ += 1;

}

// 2. int compare

const Position = {

TOP: 0,

BOTTOM: 1,

};

let _ = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

let current = i % 2 === 0 ? Position.TOP : Position.BOTTOM;

if (current === Position.TOP) _ += 1;

}

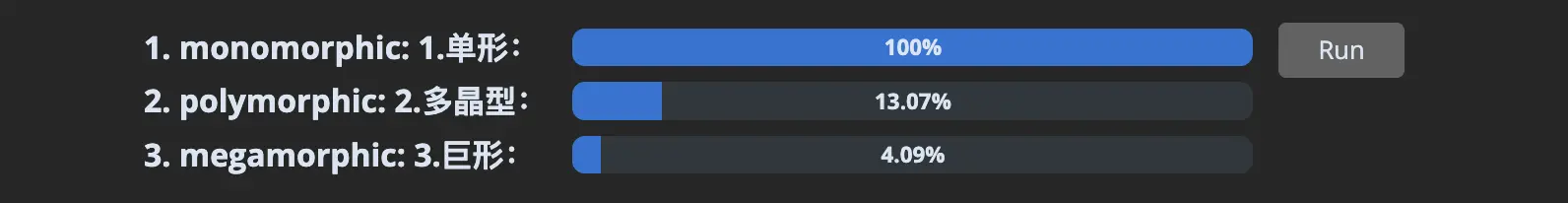

2. Avoid Different Shapes

JavaScript engines try to optimize code by assuming objects have specific shapes and that functions will receive objects with the same shapes. This allows them to store keys once for all objects of that shape and store values in a separate flat array. Expressed in JavaScript code:

// Objects the engine receives

const objects = [

{

name: 'Anthony',

age: 36,

},

{

name: 'Eckhart',

age: 42,

},

];

// Optimized internal storage structure looks like

const shape = [

{ name: 'name', type: 'string' },

{ name: 'age', type: 'integer' },

];

const objects = [

['Anthony', 36],

['Eckhart', 42],

];I've used the word "shape" to describe this concept, but be aware that you may also find "hidden class" or "map" used to describe it, depending on the engine.

For example, at runtime, if the following function receives two objects with shape { x: number, y: number }, the engine will speculate that future objects will have the same shape and generate machine code optimized for that shape.

function add(a, b) {

return {

x: a.x + b.x,

y: a.y + b.y,

};

}If we pass objects not with shape { x, y } but with shape { y, x }, the engine will need to undo its speculation, and the function will suddenly become quite slow. I'll keep my explanation brief here, because if you want more details, you should read mraleph's excellent article. But I want to emphasize that V8 in particular has 3 modes for access: monomorphic (1 shape), polymorphic (2-4 shapes), and megamorphic (5+ shapes). You really want to stay monomorphic because the performance degradation is dramatic:

Translator's note:

In order to maintain monomorphic mode for code performance, you need to ensure that objects passed to functions maintain the same shape. In JavaScript and TypeScript development, this means you need to ensure consistent property addition order when defining and manipulating objects, and avoid adding or removing properties arbitrarily. This helps the V8 engine optimize object property access. To improve performance, try to avoid changing object shapes at runtime. This involves avoiding adding or removing properties, or creating objects with the same properties in different orders. By maintaining consistency of object properties, you can help the JavaScript engine maintain efficient object access and avoid performance degradation caused by shape changes.

// setup

let _ = 0;

// 1. monomorphic

const o1 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o2 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o3 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o4 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o5 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ }; // all shapes are equal

// 2. polymorphic

const o1 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o2 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o3 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o4 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o5 = { b: _, a: 1, c: _, d: _, e: _ }; // this shape is different

// 3. megamorphic

const o1 = { a: 1, b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o2 = { b: _, a: 1, c: _, d: _, e: _ };

const o3 = { b: _, c: _, a: 1, d: _, e: _ };

const o4 = { b: _, c: _, d: _, a: 1, e: _ };

const o5 = { b: _, c: _, d: _, e: _, a: 1 }; // all shapes are different

// test case

function add(a1, b1) {

return a1.a + a1.b + a1.c + a1.d + a1.e + b1.a + b1.b + b1.c + b1.d + b1.e;

}

let result = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

result += add(o1, o2);

result += add(o3, o4);

result += add(o4, o5);

}

So what should I do?

Easy to say, hard to do: create all objects with exactly the same shape. Even something as trivial as writing React component props in a different order can trigger this.

For example, here are some simple cases I found in React's codebase, but years ago they had already experienced a higher impact from the same issue because they initialized an object with an integer and then stored a float. Yes, changing types also changes the shape. Yes, integer and float types are hidden behind number. Deal with it.

Engines can typically encode integers as values. For example, V8 represents 32-bit values with integers as compact Smi (SMall Integer) values, but floats and large integers are passed as pointers, just like strings and objects. JSC uses 64-bit encoding with double tagging, passing all numbers by value, as does SpiderMonkey, with the rest passed as pointers.

Translator's note: This encoding approach allows JavaScript engines to efficiently handle various types of numbers without sacrificing performance. For small integers, the use of Smi reduces cases where heap memory allocation is needed, improving operational efficiency. For larger numbers, although they need to be accessed through pointers, this approach still ensures JavaScript's flexibility and performance when handling various number types. This design also reflects the wisdom of JavaScript engine authors in balancing data representation and performance optimization, especially important in dynamically typed languages. Through this approach, engines can minimize memory usage and improve computation speed when executing JavaScript code.

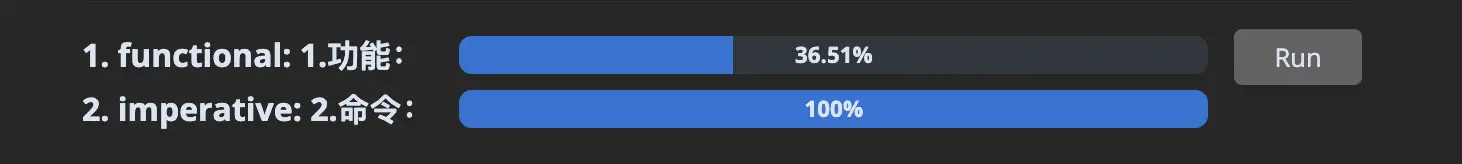

3. Avoid Array/Object Methods

I like functional programming as much as the next person, but unless you're working in Haskell/OCaml/Rust where functional code compiles to efficient machine code, functional is always slower than imperative.

const result = [1.5, 3.5, 5.0]

.map((n) => Math.round(n))

.filter((n) => n % 2 === 0)

.reduce((a, n) => a + n, 0);The problems with these methods are:

- They need to make complete copies of the array, which later need to be freed by the garbage collector. We'll explore memory I/O issues in more detail in Section 5.

- They loop N times for N operations, whereas a for loop allows looping just once.

// setup:

const numbers = Array.from({ length: 10_000 }).map(() => Math.random());

// 1. functional

const result = numbers

.map((n) => Math.round(n * 10))

.filter((n) => n % 2 === 0)

.reduce((a, n) => a + n, 0);

// 2. imperative

let result = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++) {

let n = Math.round(numbers[i] * 10);

if (n % 2 !== 0) continue;

result = result + n;

}

Object methods like Object.values(), Object.keys(), and Object.entries() suffer from similar problems because they also allocate more data, and memory access is the root of all performance issues. I swear, I'll show you in Section 5.

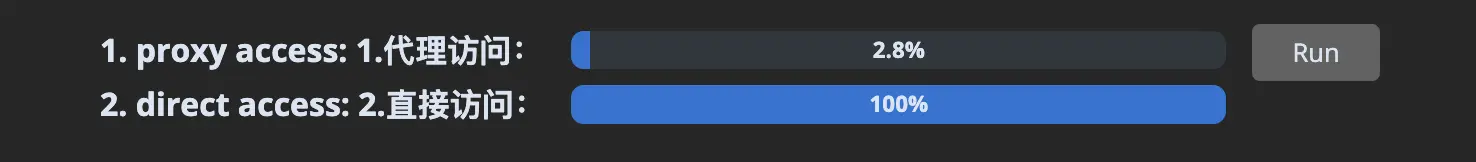

4. Avoid Indirection

Another place to look for optimization gains is any source of indirection. I can see 3 main sources:

const point = { x: 10, y: 20 };

// 1. Proxy objects are harder to optimize because their get/set functions may be running custom logic, so the engine can't make the usual assumptions.

const proxy = new Proxy(point, {

get: (t, k) => {

return t[k];

},

});

// Some engines can make the proxy cost disappear, but these optimizations are expensive and easy to break.

const x = proxy.x;

// 2. Often overlooked, but accessing objects through `.` or `[]` is also a form of indirection. In simple cases, engines can likely optimize the cost:

const x = point.x;

// But each additional access adds cost and makes it harder for engines to make assumptions about the state of "point":

const x = this.state.circle.center.point.x;

// 3. Finally, function calls also incur a cost. Engines are generally good at inlining these:

function getX(p) {

return p.x;

}

const x = getX(p);

// But there's no guarantee, especially if the function call doesn't come from a static function but from a parameter:

function Component({ point, getX }) {

return getX(point);

}The proxy benchmark is especially brutal on V8 right now. Last time I checked, proxy objects always fell back from JIT to the interpreter, and from these results, that may still be the case.

// 1. Proxy access

const point = new Proxy({ x: 10, y: 20 }, { get: (t, k) => t[k] });

for (let _ = 0, i = 0; i < 100_000; i++) {

_ += point.x;

}

// 2. Direct access

const point = { x: 10, y: 20 };

const x = point.x;

for (let _ = 0, i = 0; i < 100_000; i++) {

_ += x;

}

I also wanted to show deeply nested object access vs direct access, but engines are good at optimizing object access through escape analysis when there are hot loops and constant objects. To prevent this, I inserted some indirection.

Translator's note:

"Hot loop" refers to a loop that runs frequently during program execution -- a section of code that gets repeated many times. Because this code executes so many times, its impact on program performance is particularly significant, making it a key point for performance optimization. This term also appears later in the article.

// 1. Nested access

const a = { state: { center: { point: { x: 10, y: 20 } } } };

const b = { state: { center: { point: { x: 10, y: 20 } } } };

const get = (i) => (i % 2 ? a : b);

let result = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 100_000; i++) {

result = result + get(i).state.center.point.x;

}

// 2. Direct access

const a = { x: 10, y: 20 }.x;

const b = { x: 10, y: 20 }.x;

const get = (i) => (i % 2 ? a : b);

let result = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 100_000; i++) {

result = result + get(i);

}

5. Avoid Cache Misses

This point requires some low-level knowledge, but it has implications even in JavaScript, so I'll explain. From the CPU's perspective, fetching memory from RAM is slow. To speed things up, it primarily uses two optimizations.

5.1 Prefetching

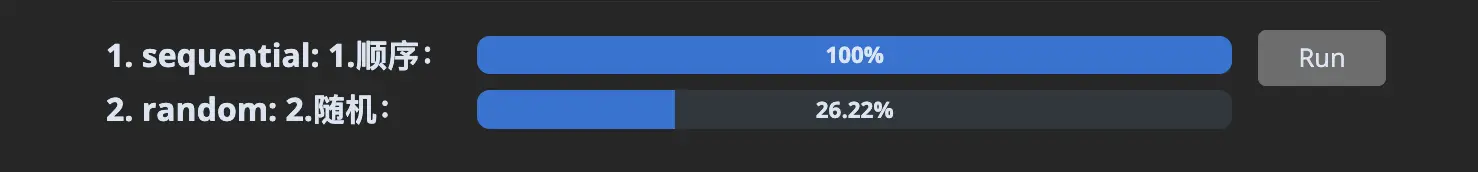

The first is prefetching: it fetches more memory ahead of time, hoping that's what you're interested in. It always guesses that if you request a memory address, you'll be interested in the memory region that immediately follows. Therefore, accessing data sequentially is key. In the following example, we can observe the impact of accessing memory in random order.

// setup:

const K = 1024;

const length = 1 * K * K;

// These points are created one after another, so they are allocated sequentially in memory.

const points = new Array(length);

for (let i = 0; i < points.length; i++) {

points[i] = { x: 42, y: 0 };

}

// This array contains the same data as above, but randomly shuffled.

const shuffledPoints = shuffle(points.slice());

// 1. Sequential

let _ = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < points.length; i++) {

_ += points[i].x;

}

// 2. Random

let _ = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < shuffledPoints.length; i++) {

_ += shuffledPoints[i].x;

}

So what should I do?

Applying this concept in practice can be the most difficult, since JavaScript doesn't have a way to specify where objects sit in memory. But you can, like the example above, use this knowledge to your advantage -- for instance, operate on data before reordering or sorting. You can't assume that objects created sequentially will stay in the same location after some time, since the garbage collector may move them. But there's one exception: numeric arrays, preferably TypedArray instances:

For a more detailed example, see this link*.

- Note that it contains some now-outdated optimizations, but is still generally accurate.

Translator's note:

JavaScript's TypedArray instances provide an efficient way to handle binary data. Compared to regular arrays, TypedArrays are not only more memory-efficient, but they access contiguous memory regions, enabling higher performance during data operations. This is closely related to the prefetching concept, since processing contiguous memory blocks is typically faster than random memory access, especially when dealing with large amounts of data. For example, if you're processing large amounts of numerical data, such as image processing or scientific computing, using Float32Array or Int32Array and other TypedArrays can give you better performance. Since these arrays directly manipulate memory, they can read and write data faster, especially during sequential access. This not only reduces JavaScript runtime overhead but also leverages modern CPU prefetching and caching mechanisms to accelerate data processing.

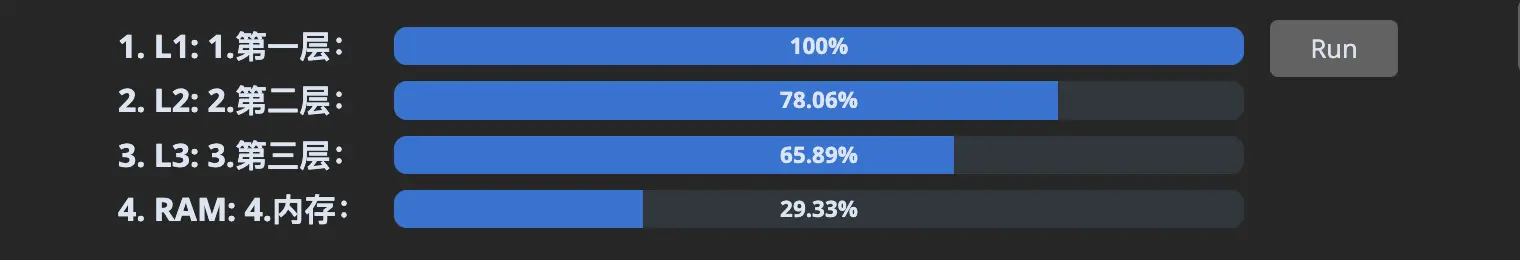

5.2 Caching in L1/2/3

The second optimization CPUs use is L1/L2/L3 caches: these are like faster RAMs, but also more expensive, so they are much smaller in capacity. They contain RAM data but act as LRU caches. Data enters when it's "hot" (being processed) and is written back to main RAM when new working data needs the space. So the key here is to use as little data as possible, keeping the working dataset in the fast caches. In the following example, we can observe the effect of busting each successive cache.

// setup:

const KB = 1024;

const MB = 1024 * KB;

// These are approximate sizes that fit these caches. If you're not getting the same results on your computer, it's probably because your sizes are different.

const L1 = 256 * KB;

const L2 = 5 * MB;

const L3 = 18 * MB;

const RAM = 32 * MB;

// We'll access the same buffer for all test cases, but we'll only access entries from 0 to "L1" for the first case, 0 to "L2" for the second, and so on.

const buffer = new Int8Array(RAM);

buffer.fill(42);

const random = (max) => Math.floor(Math.random() * max);

// 1. L1

let r = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

r += buffer[random(L1)];

}

// 2. L2

let r = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

r += buffer[random(L2)];

}

// 3. L3

let r = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

r += buffer[random(L3)];

}

// 4. RAM

let r = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

r += buffer[random(RAM)];

}

So what should I do?

Ruthlessly eliminate every bit of data or memory allocation you can. The smaller the dataset, the faster the program runs. Memory I/O is the bottleneck of 95% of programs. Another good strategy is to divide your work into chunks and make sure you process one small dataset at a time.

For more details on CPU and memory, refer to this link.

- About immutable data structures -- Immutability is great for clarity and correctness, but in terms of performance, updating immutable data structures means copying containers, which leads to more memory I/O that flushes caches. You should avoid immutable data structures whenever possible.

- About the

...spread operator -- It's very convenient, but every time you use it, you create a new object in memory. More memory I/O, slower caches!

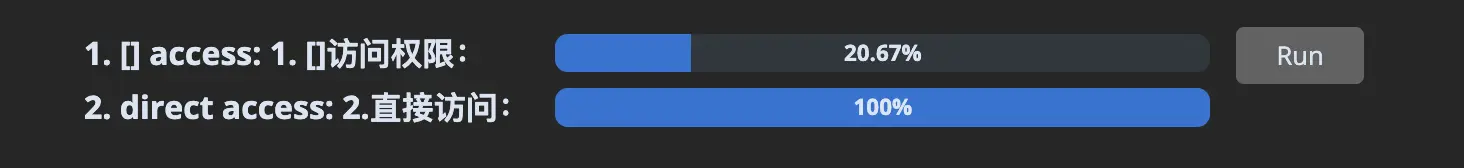

6. Avoid Large Objects

As discussed in Section 2, engines use shapes to optimize objects. However, when shapes become too large, engines have no choice but to use regular hash tables (like Map objects). As we saw in Section 5, cache misses can significantly degrade performance. Hash tables are prone to this because their data is typically randomly and evenly distributed across the memory region they occupy. Let's see how this user map indexed by user ID performs.

// setup:

const USERS_LENGTH = 1_000;

// setup:

const byId = {};

Array.from({ length: USERS_LENGTH }).forEach((_, id) => {

byId[id] = { id, name: 'John' };

});

let _ = 0;

// 1. [] access

Object.keys(byId).forEach((id) => {

_ += byId[id].id;

});

// 2. direct access

Object.values(byId).forEach((user) => {

_ += user.id;

});

We can also observe how performance continuously degrades as the object size increases:

// setup:

const USERS_LENGTH = 100_000;

So what should I do?

As mentioned above, avoid frequently indexing large objects. It's better to convert the object to an array beforehand. Organizing IDs on the model can help you organize data since you can use Object.values() instead of needing to reference a key map to get the ID.

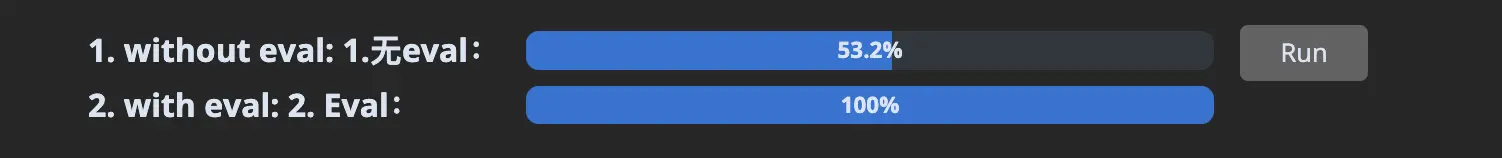

7. Use eval

Some JavaScript patterns are hard for engines to optimize, and by using eval() or its derivatives, you can make those patterns disappear. In this example, we can observe how using eval() avoids the cost of creating objects with dynamic keys:

// setup:

const key = 'requestId';

const values = Array.from({ length: 100_000 }).fill(42);

// 1. without eval

function createMessages(key, values) {

const messages = [];

for (let i = 0; i < values.length; i++) {

messages.push({ [key]: values[i] });

}

return messages;

}

createMessages(key, values);

// 2. with eval

function createMessages(key, values) {

const messages = [];

const createMessage = new Function('value', `return { ${JSON.stringify(key)}: value }`);

for (let i = 0; i < values.length; i++) {

messages.push(createMessage(values[i]));

}

return messages;

}

createMessages(key, values);

Translator's note:

In the eval version (implemented via the Function constructor), the example first creates a function that dynamically generates an object with a dynamic key and a given value. Then this function is called in a loop to create the message array. This approach reduces runtime computation and object creation overhead by pre-compiling the object-generating function. While using eval and the Function constructor can avoid certain runtime overhead, they also introduce potential security risks because they can execute arbitrary code. Additionally, dynamically evaluated code can be difficult to debug and optimize since it's generated at runtime and the JavaScript engine may not be able to perform effective optimization in advance. Therefore, although this example demonstrates a performance optimization technique, in practice it's recommended to find other methods to optimize performance while maintaining code safety and maintainability. In most cases, avoiding the need for massive dynamic object creation and improving performance through static analysis and code refactoring would be better choices.

Another great use case for eval is compiling a filter predicate function where you can discard branches you know will never be executed. Generally, any function that will run in a very hot loop is a candidate for this optimization.

Obviously, the usual warnings about eval() apply: don't trust user input, sanitize anything passed into eval() code, and don't create any XSS possibilities. Also note that some environments don't allow access to eval(), such as browser pages with CSP.

8. Use Strings Carefully

We've already seen above that strings are more expensive than they appear. Well, I have good news and bad news here, and I'll announce them in the only logical order (bad first, then good): strings are more complex than they appear on the surface, but they can also be used very efficiently.

String manipulation is a core part of JavaScript due to its context. To optimize string-heavy code, engines need to be creative. What I mean is they must represent string objects with multiple string representations in C++ depending on the use case. There are two general cases worth worrying about, as they apply to V8 (by far the most common engine), and generally to other engines as well.

First, strings concatenated with + don't create copies of the two input strings. The operation creates pointers to each substring. In TypeScript terms, it would look like this:

class String {

abstract value(): char[] {}

}

class BytesString {

constructor(bytes: char[]) {

this.bytes = bytes;

}

value() {

return this.bytes;

}

}

class ConcatenatedString {

constructor(left: String, right: String) {

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

}

value() {

return [...this.left.value(), ...this.right.value()];

}

}

function concat(left, right) {

return new ConcatenatedString(left, right);

}

const first = new BytesString(['H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', ' ']);

const second = new BytesString(['w', 'o', 'r', 'l', 'd']);

// See, no array copies!

const message = concat(first, second);Second, string slices also don't need to create copies: they can simply point to a range within another string. Continuing the example above:

class SlicedString {

constructor(source: String, start: number, end: number) {

this.source = source;

this.start = start;

this.end = end;

}

value() {

return this.source.value().slice(this.start, this.end);

}

}

function substring(source, start, end) {

return new SlicedString(source, start, end);

}

// This represents "He", but it still contains no array copies.

// It's a SlicedString to a ConcatenatedString to two BytesString

const firstTwoLetters = substring(message, 0, 2);But here's the problem: once you need to start mutating those bytes, that's when you start paying the copy cost. Suppose we go back to our String class and try to add a .trimEnd method:

class String {

abstract value(): char[] {}

trimEnd() {

// `.value()` here might call our Sliced->Concatenated->2*Bytes string!

const bytes = this.value();

const result = bytes.slice();

while (result[result.length - 1] === ' ') result.pop();

return new BytesString(result);

}

}So let's jump to an example comparing mutation operations vs. concatenation-only operations:

// setup:

const classNames = ['primary', 'selected', 'active', 'medium'];

// 1. mutation

const result = classNames.map((c) => `button--${c}`).join(' ');

// 2. concatenation

const result = classNames.map((c) => 'button--' + c).reduce((acc, c) => acc + ' ' + c, '');

So what should I do?

In general, avoid mutations as much as possible. This includes methods like .trim(), .replace(), etc. Consider how to avoid using these methods. In some engines, template literals may also be slower than +. This is currently the case in V8, but may not be in the future, so always benchmark.

A note about the SlicedString above: if a small substring of a large string remains in memory, it may prevent the garbage collector from collecting the large string! So if you're processing large text and extracting small strings from it, you may be leaking significant amounts of memory.

const large = Array.from({ length: 10_000 })

.map(() => 'string')

.join('');

const small = large.slice(0, 50);

// ^ will keep aliveThe solution here is to use a mutation method in our favor. If we use one on small, it will force a copy, and the old pointer to large will be lost:

// replace a token that doesn't exist

const small = small.replace('#'.repeat(small.length + 1), '');For more details, see string.h on V8 or JSString.h on JavaScriptCore.

About string complexity -- I've skimmed over some things, but there are many implementation details that add to string complexity. Each string representation typically has a minimum length. For example, concatenated strings may not be used for very small strings. There are also sometimes limitations, such as avoiding substrings of substrings. Reading the C++ files linked above, even just the comments, gives a good understanding of implementation details.

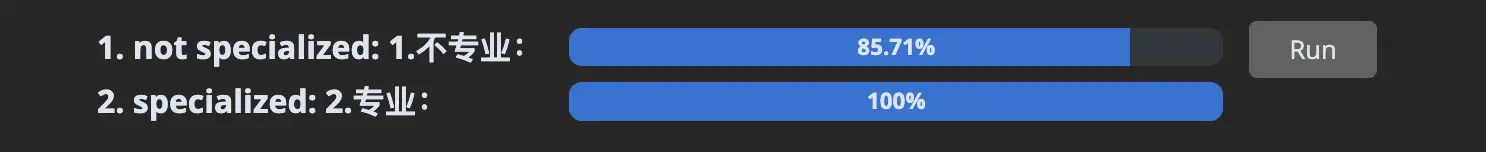

9. Specialize

An important concept in performance optimization is specialization: adapting logic to the constraints of a specific use case. This usually means figuring out which cases are likely to occur and coding for those cases.

Suppose we're a merchant who sometimes needs to add tags to a product list. From experience, we know tags are usually empty. Knowing this, we can specialize our function for this case:

// setup:

const descriptions = ['apples', 'oranges', 'bananas', 'seven'];

const someTags = {

apples: '::promotion::',

};

const noTags = {};

// Convert products to string, including their tags if applicable

function productsToString(description, tags) {

let result = '';

description.forEach((product) => {

result += product;

if (tags[product]) result += tags[product];

result += ', ';

});

return result;

}

// Specialize it now

function productsToStringSpecialized(description, tags) {

// We know `tags` is likely to be empty, so we check once upfront and can then remove the `if` check from the inner loop

if (isEmpty(tags)) {

let result = '';

description.forEach((product) => {

result += product + ', ';

});

return result;

} else {

let result = '';

description.forEach((product) => {

result += product;

if (tags[product]) result += tags[product];

result += ', ';

});

return result;

}

}

function isEmpty(o) {

for (let _ in o) {

return false;

}

return true;

}

// 1. not specialized

for (let i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

productsToString(descriptions, someTags);

productsToString(descriptions, noTags);

productsToString(descriptions, noTags);

productsToString(descriptions, noTags);

productsToString(descriptions, noTags);

}

// 2. specialized

for (let i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

productsToStringSpecialized(descriptions, someTags);

productsToStringSpecialized(descriptions, noTags);

productsToStringSpecialized(descriptions, noTags);

productsToStringSpecialized(descriptions, noTags);

productsToStringSpecialized(descriptions, noTags);

}

This optimization can give you modest improvements, but they accumulate. They're a good complement to more important optimizations like shapes and memory I/O. But be aware that specialization can work against you if your conditions change, so be careful when applying it.

Branch prediction and branchless code -- Removing branches from code can greatly improve performance. For more details on branch predictors, read the classic Stack Overflow answer: Why is processing a sorted array faster than processing an unsorted array?

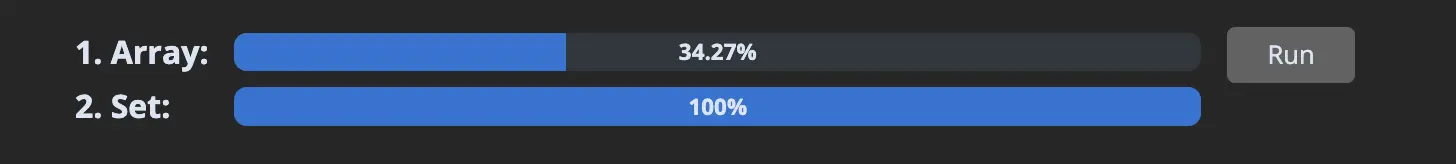

10. Data Structures

I won't go into details about data structures because that would require a separate article. But note that using the wrong data structure for your use case can have a bigger impact than any of the optimizations above. I recommend familiarizing yourself with native data structures like Map and Set, and learning about linked lists, priority queues, trees (RB and B+), and tries.

As a quick example, let's compare Array.includes vs Set.has on a small list:

// setup:

const userIds = Array.from({ length: 1_000 }).map((_, i) => i);

const adminIdsArray = userIds.slice(0, 10);

const adminIdsSet = new Set(adminIdsArray);

// 1. Array

let _ = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < userIds.length; i++) {

if (adminIdsArray.includes(userIds[i])) {

_ += 1;

}

}

// 2. Set

let _ = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < userIds.length; i++) {

if (adminIdsSet.has(userIds[i])) {

_ += 1;

}

}

As you can see, the choice of data structure can make a very large difference.

As a real-world example, I once encountered a scenario where swapping an array for a linked list reduced a function's runtime from 5 seconds to 22 milliseconds.

11. Benchmarking

I saved this section for last for one reason only: I needed to build credibility through the interesting parts above. Now that I have it (hopefully), let me tell you that benchmarking is the most important part of optimization work. It's not only the most important, but also difficult. Even with 20 years of experience, I still sometimes create flawed benchmarks or misuse profiling tools. So by all means, do your best to create benchmarks correctly.

11.0 Top-Down

Your top priority should always be optimizing the functions/code paths that take up the largest portion of runtime. If you spend time optimizing anything besides the most important parts, you're wasting time.

11.1 Avoid Micro-benchmarks

Run your code in production mode and optimize based on those observations. JS engines are very complex, and their behavior in micro-benchmarks is often different from real-world scenarios. For example, consider this micro-benchmark:

const a = { type: 'div', count: 5 };

const b = { type: 'span', count: 10 };

function typeEquals(a, b) {

return a.type === b.type;

}

for (let i = 0; i < 100_000; i++) {

typeEquals(a, b);

}If you pay attention, you'll notice that the engine will specialize the function for shape { type: string, count: number }. But does this hold in real-world use? Will a and b always be this shape, or might you receive any shape? If you receive many shapes in production, the function will behave differently.

11.2 Doubt Your Results

If you've just optimized a function and it now runs 100x faster, be skeptical. Try to disprove your results, try running in production mode, stress test it. Similarly, be suspicious of your tools. Merely observing a benchmark with devtools can change its behavior.

11.3 Choose Your Target

Different engines optimize certain patterns better than others. You should benchmark against the engines relevant to you and prioritize which engine is more important. Here's a real-world example in Babel where improving V8 meant degrading JSC performance.

12. Profiling and Tools

Various discussions about profiling and developer tools.

12.1 Browser Pitfalls

If you're profiling in the browser, make sure you're using a clean, blank browser profile. I even use a separate browser for this. If you have browser extensions enabled during profiling, they will mess up your measurements. React devtools in particular can significantly affect results, making code rendering appear much slower than what's actually presented to users.

12.2 Sample vs Structural Profiling

Browser profiling tools are sampling-based profilers that periodically sample your call stack. This has a big drawback: some very small, frequently called functions may be called between these samples and may be severely underreported in the stack chart you see. Mitigate this by using Firefox devtools' custom sampling interval or Chrome devtools' CPU throttling feature.

12.3 Common Tools for Performance Optimization

Beyond regular browser devtools, knowing about these options can be helpful:

- There are many experimental flags in Chrome devtools that can help you find the cause of slowness. The style invalidation tracker is very useful when you need to debug style/layout recalculations in the browser. https://github.com/iamakulov/devtools-perf-features

- The deoptexplorer-vscode extension lets you load V8/chromium log files to understand when your code triggers deoptimization, such as when you pass different shapes to functions. You don't need this extension to read log files, but it makes the experience much more pleasant. https://github.com/microsoft/deoptexplorer-vscode

- You can also compile debug shells for each JS engine to understand in more detail how they work. This allows you to run perf and other low-level tools, and also inspect the bytecode and machine code generated by each engine. V8 example | JSC example | SpiderMonkey example (missing)

喜欢的话,留下你的评论吧~