This article has been machine-translated from Chinese. The translation may contain inaccuracies or awkward phrasing. If in doubt, please refer to the original Chinese version.

I thought some of my previous thoughts were quite interesting, so I decided to polish them up and post them as a quick blog entry. The title sounds intimidating, but it really applies to any field.

A while ago, I saw someone discussing “how to systematically learn front-end development,” mentioning that many aspects of front-end architecture haven’t changed in years, and that one should focus more on overall architectural design and controlling code complexity.

I strongly agree with this take, but I’d like to add a few points. Front-end is actually an incredibly broad field. Drill down into its sub-domains and you’ll find consumer-facing (toC) front-end, enterprise (toB) front-end, infrastructure front-end, WebGL front-end, and more. To learn systematically, you first need to identify your direction: are you focusing on user experience, diving deep into business logic, or investing in toolchain development? Different directions require completely different areas of expertise.

Moreover, front-end is not static. Users aren’t limited to enterprise system users — there are also many who focus on creative expression and visual presentation. Game front-end is front-end. Future VR/XR pages are front-end. Browser extension/mini-program development is front-end. Node.js development also counts as front-end — and if you stretch it a bit further, cross-platform development is arguably another extension of front-end.

If I were to give advice from a toC front-end perspective: front-end animation, CSS, Three.js, interaction design, performance optimization, SEO… each of these has an entire knowledge system behind it, and digging deep into any one of them is an endless journey. As for technology choices, they often need to follow business requirements — there’s no one-size-fits-all “best practice.”

On the other hand, front-end technology itself is continuously changing. Take CSS, for example — in recent years, it has been actively working to eliminate the need for preprocessors and become more user-friendly: native nesting syntax, @if functions, anchor positioning, container queries, shape() functions… Many things we used to rely on preprocessors or hacks to achieve are gradually becoming standardized. Browser compatibility is also steadily improving — even Safari is making an effort to keep up. For instance, WebGPU will finally be supported in iOS 26 (though I complain about Safari all the time, it’s genuinely good to see more features being supported and progressive enhancement becoming more viable).

While front-end still has many terrible legacy issues, we should also recognize that it’s getting better. If you’re interested in this topic, I recommend a great article I read before: HTML is Dead, Long Live HTML — very insightful.

So in my view, the “variables” in front-end are more about the rapid iteration of external technical forms — CSS standards constantly updating, build tools being replaced by newer ones, framework ecosystems rising and falling. Webpack is popular today, Vite might take over tomorrow. You just understood Vue 2, and Vue 3’s Composition API is already mainstream. These changes are surface-level and tool-oriented, and they’re exactly what outsiders notice and complain about most.

What remains “constant” are the underlying problems and core design principles: how to manage state, how to decompose components, how to optimize rendering efficiency, how to implement maintainable code structures, how to ensure consistency in user experience. These challenges have existed since the early jQuery era through to today’s React and Solid.js. They’ve never disappeared — they simply resurface in different syntax and architectural paradigms, in any language.

I believe the evolution of front-end development is essentially an “evolution of expression” rather than a “replacement of problems.”

Therefore, mastering front-end isn’t about blindly chasing every new tool or framework, but about identifying those enduringly constant principles amidst the change — understanding them is what truly builds your own transferable technical capabilities.

One last thing I want to say: front-end is far more than a competition of “proficiency.” It has both the surface of interfaces and the depth of engineering. It demands attention to interaction details while maintaining architectural stability. Writing an animation can be as simple as setInterval, or it can go deep into rendering principles, performance hierarchies, and visual algorithms. Choosing “how to do it” is itself a process of technical judgment and architectural thinking.

In any craft, repetition and accumulation form the foundation. But if you think front-end is merely about “slicing pages, tweaking styles, and writing interactions,” you’re truly underestimating this field.

The so-called “lack of technical depth” might simply mean you haven’t yet encountered truly complex problems.

Writing to this point, I realize this actually applies to any direction, hahahaha.

Sometimes I wonder: perhaps the true charm of front-end lies precisely in how close it is to “expression.”

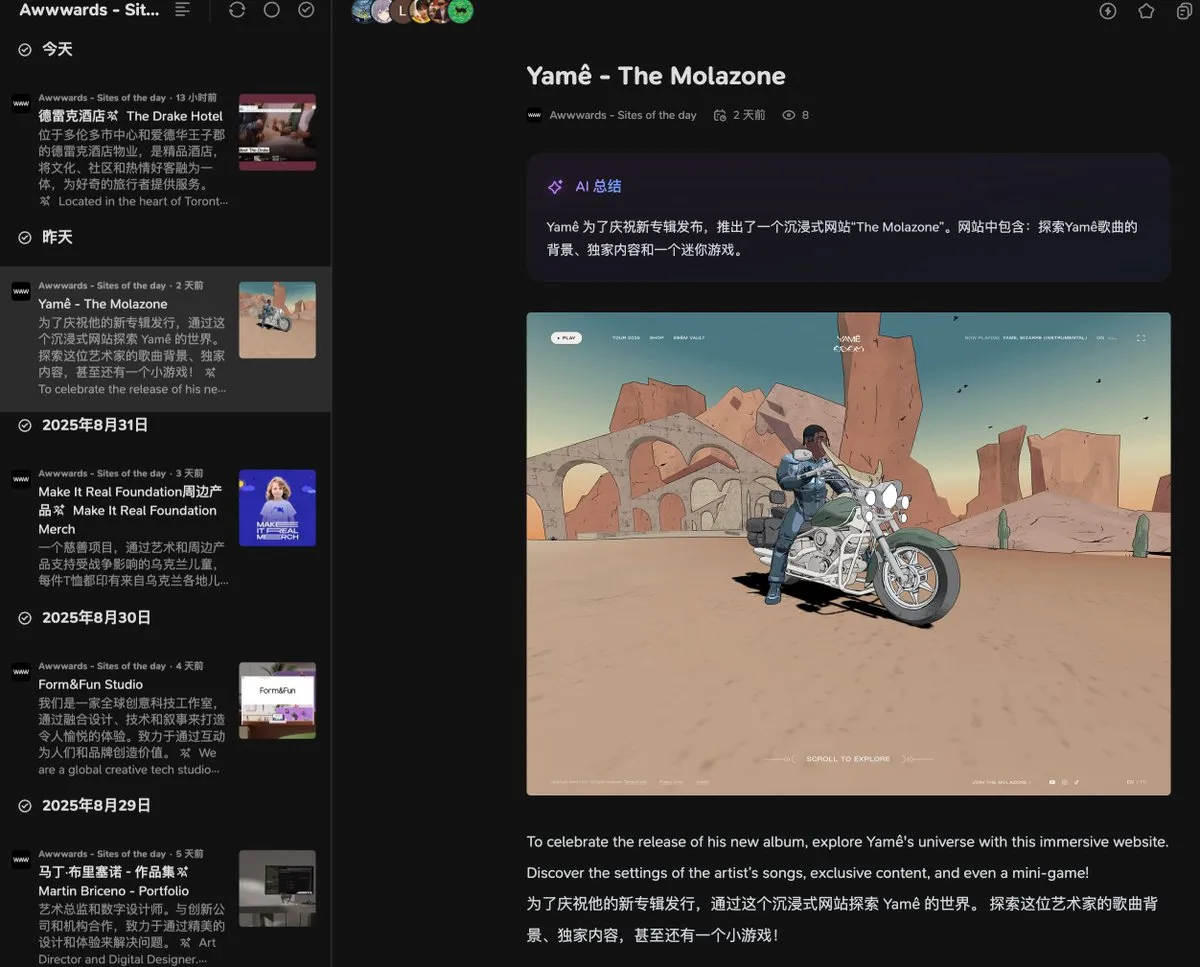

After seeing so many beautiful small websites from overseas, I genuinely feel a bit envious — an album, an artist, a charitable cause, a corner hotel, even a local food brand, all get lovingly crafted little websites with unique character. They aren’t necessarily complex, but they’re full of personality, carrying the warmth and ingenuity of their creators.

This culture of “anything can get its own little showcase website” reminds you of what the Web originally looked like — always criticized by some, always loved by others. Front-end isn’t just a tool for implementing requirements; it can also be a canvas for creative expression.

Perhaps this is exactly what keeps attracting people to front-end technology: it always carries people’s pursuit of beauty, expression of creativity, and the belief that every idea deserves to be presented well.

喜欢的话,留下你的评论吧~